MSL Winter School 2025

SEMINAR

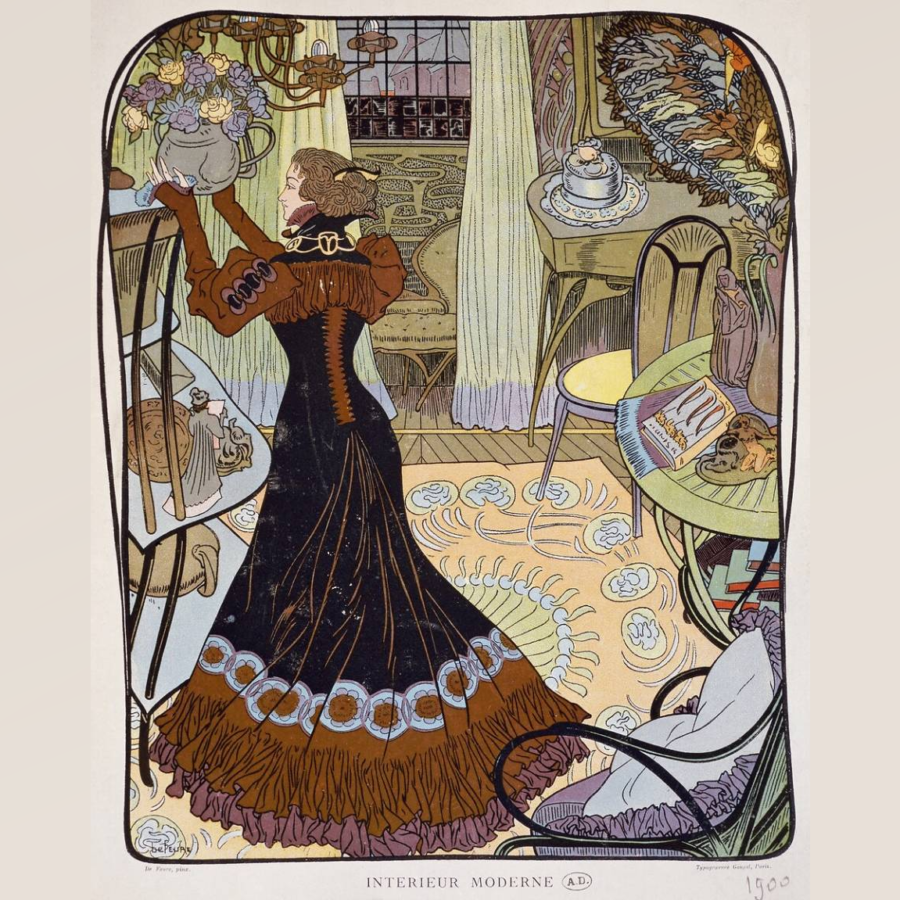

DECORATION

⠀

Lecturer: Angela Hesson

Thursdays 6–8pm, 19 June – 17 July 2025, Multipurpose Room 2, Kathleen Syme Library, Carlton, Melbourne (in-person only, recordings uploaded each week)

When, in 1884, French writer Rachilde described the ‘profane interior’ of a particular Paris house, she provided, perhaps knowingly, the ideal descriptor and metaphor, not only for the edifice itself, but also for the peculiar person and personality of her protagonist. Raoule, the exquisite, sadistic (anti)hero(ine) of Rachilde’s Monsieur Venus, is definable by the things she chooses to have about her. Her identity is expressed visibly, tangibly, decoratively; her accessories, her ornaments, even her lover, emerge as manifestations, perhaps symptoms, of her nature. Here, surface is evoked to figure its own kind of depth, and excess to convey considerable subtlety.

In the wake of the Arts and Crafts movement and with the evolution of Decadence and Aestheticism in the late nineteenth century, the subject of decoration was subject to some radical reassessments. From the 1860s, when the first household design manuals emerged, the middle-class homemaker was encouraged, indeed instructed, to take a passionate interest in the careful beautification of both her home and herself, offering pleasure and comfort to family and friends, as well as reassuring moral structure. But at the approach of the fin de siècle, processes of decoration, and the ways in which these processes were described, became both more fluid and more coded, with the decorous principles of household management touched by the creeping tint of fetishism.

This winter we’re staying inside to examine the subject of decoration through a selection of fin-de-siècle sources, from practical household design manuals, to politicised short stories, to classic novels, to lavishly camp novellas. Through these texts and some associated images and objects, we’ll consider the subtle interactions of surface and depth, detail and economy, beauty and ugliness, high and low culture, masculine and feminine, sacred and profane; and question in turn the extent to which (and to what ends) fin-de-siècle writing interrogates, undermines, or embellishes the sense of simple opposition or duality implied in these pairings.

SEMINAR

The world turned day-glo: weird bodies in 20th century science fiction

Lecturer: James Macaronas

Tuesdays 6–8pm, 17 June – 15 July 2025, Week 1: Meeting Room 3, Weeks 2-4: Multipurpose Room 1, Week 5: Activity Room 1, Kathleen Syme Library, Carlton, Melbourne (in-person only, recordings uploaded each week)

The period from the close of the fin de siècle to the aftermath of the Cold War bore witness to a radical shift in human relation to the world around us. Factors precipitating this shift included the discovery of new worlds, at both solar and subatomic scales; the continued implementation of mass industrialisation (parallel to a growing awareness of its impact on the planet); and the emergence of the computer in everyday life. In anglophone literature, it’s the genre of science fiction (SF) that most explicitly chronicles the transformation of the human (and nonhuman) subject in this crucible of technological change.

From the deadly embrace of alien vampires to the radically altered bodies of the cybernetic age, this short course zeroes in on landmark texts and writers in 20th century SF – many of whom remain overlooked in more mainstream literary histories – to explore the ways they sought to express the new reality around them. Our particular focus is the bodies imagined within these texts, avatars for a strange new world that also challenge some of the commonplace understandings of SF. These markedly weird figures draw attention to the genre’s fascination with what critic Adam Roberts terms the “encounter with difference”. This in turn enables us to access radical philosophical and political implications of texts that might otherwise be regarded as distant from our own cultural moment.

So, strap on your spacesuit! The countdown is on for a journey into the stratosphere of fiction’s outer limits, where we come face to face with the high strangeness of our technological selves.